Sleep Rescue Kit

It’s 1:08 am and I can’t sleep.

The numbers on the clock are small, but they light the room. The fan turns unevenly above me, one blade a little lower than the others, making a faint click each time it completes a circle. Somewhere in the distance, a bike passes and fades. On the bedside table, the remains of my sleep-rescue kit sit in the edge of my vision like day old plate I never cleaned up.

I named it that once, half as a joke, back when the table was crowded. A photo taken quickly, sent across a chat window, with the caption: “Welcome to my sleep-rescue kit.” You could barely see the wood then. There was a full box of melatonin strips, in a nice white and blue metal box. A bottle of magnesium tablets. A box of chamomile teabags, corner torn open, the sachets standing in neat, anxious rows. A strip of prescription pills in polished foil. Even a cheap lavender roll-on someone had sworn by. It looked less like a “kit” and more like a cry for help written in the language of over-the-counter medication.

If sleep could be bribed, I was definitely overpaying.

She laughed when she saw it. I remember that clearly, more clearly than I remember…ah whatever it is that I ought to be remembering. It was a laugh that escaped before she could regulate it, a sound that belonged to a version of her that didn’t take everything so seriously. “You’re over-prepared,” she said. “Welcome to the other side, my friend.” As if I had just arrived, suitcase in hand, instead of having lived here for years.

I didn’t know her well then. All I knew was what our mutual friend had said, that we were “the same kind of crazy.” It sounded almost theatrical when he said it over coffee. I thought it was a line meant to make the introduction sound interesting, like adding unnecessary adjectives to an otherwise ordinary sentence. I said something neutral and changed the topic. I didn’t realise he was giving me the last honest summary I would get.

We started with late-night calls because that was when both of us were available and neither of us was willing to admit how much we were waiting for them. The first few times, the conversation moved cautiously around the usual introduction points. Where we worked. What we did. The sort of plain facts that fit easily in a sentence. It stood there, polite and nonthreatening, until she decided she was bored with it.

“Let’s just skip to the real things,” she said one night. “We can do the regular questions later, if there’s anything left to say.” She suggested we trade damage, the way people trade childhood stories. “Trauma dump” she called it. I remember thinking it was a strange way to build trust. But I also remember that I didn’t object.

She went first. She talked about the man who hit her, the first one. Not in great detail, not at first, just enough to establish that his temper had a radius. Then the other man, the one the couples counselor told her to run from, not walk. She mentioned the “couples counselor” almost in passing, like someone quoting a weather report. The facts were all there, but the feeling had been filed down from the retelling. You could tell there had been tears, once. Not anymore.

I did my part. I spoke about the marriage that left me tired in a way sleep wouldn’t touch. I gave her pieces of the story, never all at once, as if I didn’t quite trust my own memory to be fair. She listened more than she spoke, on those nights. I could hear it in her breathing. The little pause when something I said matched something she had never said out loud.

The subject of sleep entered the conversation almost on its own. It usually does when people like us are involved. She mentioned casually that she slept every two days, when her body finally stopped arguing with exhaustion. It wasn’t a choice, she said, it was more like being switched off. I told her I understood. My own sleep had long since stopped obeying clocks. I slept when I broke. I did not sleep while I was breaking.

There was a silence on the line then, not the usual kind, not the one where you’re both looking for the next topic. This one settled between us as something understood. Two people who could not do the simplest thing the body asked for, and who recognized the same failure in each other without needing proof.

That was when she started prescribing.

She told me about melatonin first, as if she were revealing a secret. Then magnesium. Then chamomile tea. Her voice took on a strange brightness as she listed them, the cheer of someone who has read all the instructions at the back of the packet and wants to believe they work. People like us don’t need supplements, we need a full system reboot, but I let her have her optimism. Magnesium was doing its best. I wasn’t.

I let her finish, then took the picture of the kit and sent it. She answered with that laugh and that line, welcoming me to a side I had been on so long that I had forgotten there was any other.

We fell into a rhythm after that. The calls were not daily, but frequent enough that my body started measuring time by them. I began to recognise the sound of her room through the phone, a distant traffic murmur, sometimes a fan, sometimes the silence of closed windows. I learned the way she inhaled before saying something she was afraid I might mishandle. I heard the faint scratch of a pen she kept in her hand out of habit, tapping it against a notebook I never saw. Sometimes, when she was thinking about how to phrase something difficult, I could hear the cap being clicked on and off, a soft plastic note marking her hesitation.

I told myself we were just two night people talking. That nothing was happening. That this was a passing companionship built on shared sleeplessness and familiar types of hurt. Denial is very efficient when you frame it as modesty.

The night that matters did not arrive with any warning. It did not feel like a turning point as it happened. It felt like any other late call, slightly frayed at the edges, both of us a little more tired, a little less guarded. If I had not looked at the clock later, I might have missed the time completely. Now it is the only time I seem to notice.

It was 1:08 am.

We had been talking about nothing in particular, the way you do when it’s too late for big subjects but too early to hang up. There was a softness in her voice that night, a kind of weary gentleness that I had not heard before. She asked about my day, and I gave an answer that said little but took a long time to say. She made a dry remark and laughed once, then let the sound die without pushing it any further. The quiet that followed did not feel awkward. It felt like a room in which someone was building up the courage to rearrange the furniture.

When she finally spoke, her voice had dropped the last of its performance.

“Do people like us ever get to rest?” she asked.

It was not a dramatic question. She didn’t load it with emphasis. It came out flat, as though she had been turning it over alone for a long time and had only now decided to let it out into the space between us. But the words themselves carried more weight than the tone let show.

I remember, with almost disgusting clarity, what passed through my mind in the seconds after she said it.

There were obvious answers, ready-made phrases that any decent person should have been able to reach for. I could have said yes. Yes, with help. Yes, with time. Yes, with the right people. I could have handed her some cautious hope, something small and fragile and maybe untrue, but at least not nothing. That answer would have meant saying that I believed rest was not only for the untouched, that people like us were not permanently sentenced to high alert.

I could have said no. Not really. I could have matched her exhaustion with my own, told her that people who have lived as we had do not find easy rest, that our bodies remember too much. It would have been cruel, but it would have been honest in the only way I knew how to be then. It would have at the very least said, you are not broken for feeling this tired, the world is not built for people who have been hit too many times.

I could have dodged it with a joke. I could have said something about rest being a rumour, or told her that people like us only rest when we collapse and hope nobody notices. It would not have answered the question, but it would have kept the moment light, spared me from standing in the place she was asking me to stand.

I could have taken the risk and said, “With me, maybe.” Those three words would have opened a door I had spent weeks standing in front of, pretending it was a wall. It would have meant offering myself as a place, not of cure, I was not foolish enough to pretend that, but of temporary shelter. It would have been reckless. It might have been wrong. It would have been more honest than the silence I chose.

Because what I actually did was nothing.

My throat closed around the first syllable of an answer and then refused to continue. I remember the pressure of it, the way the body can betray you with the simplest refusal. The room around me sharpened in that silence. The fan’s uneven click suddenly grew louder, each rotation spelling out my failure in a sound I now cannot unhear. My thumb, restless, found the edge of the melatonin strip box on the table and pressed against it, producing a soft crackle of frail metal and foil. I was aware of every small noise in that room except my own voice.

I do not know how many seconds passed. It was not short enough to be polite. It was long enough to become an answer.

On the other end, I heard her inhale, then a long, measured exhale. She didn’t click her pen.

“It’s okay,” she said after a moment.

She did not mean that it was okay. She meant that she had seen something she did not want to see and was closing the file before it hurt her. Her tone was not confrontational, if anything, it sounded like she was disappointed with herself for asking in the first place.

We moved on. Or at least, we pretended to. She changed the subject with a softness that felt like the careful handling of a sharp glass shard. We finished the call the way we always did, with some light remark meant to cushion the end. If anyone had been listening only to the last few minutes, they would have thought it was an ordinary night.

It’s now, in this room, with the fan and the clock, that I cannot escape that moment. That question has not finished being asked. Her voice still hangs there, inside the silence I left.

The drift, after that, was also not dramatic. It was a series of small subtractions. One less message here. A shorter reply there. A call that ended ten minutes earlier than usual. She stopped asking things that required me to stand anywhere firm. I stopped letting the conversation wander near the edges where real answers might be needed. We did not have a fight. We did not break. We simply behaved as if nothing had happened, and in doing so, let everything happen.

In those months, I used up most of the sleep-rescue kit without ever deciding to. A strip of melatonin on a night when my chest felt too tight. Two magnesium tablets on a week where the days blurred. Chamomile on evenings where I wanted to perform the ritual of trying to sleep, even if I knew it wouldn’t work. Piece by piece, pill by pill, bag by bag, the kit thinned out.

What I did not do was buy more.

She reappeared one evening as if she were an old song that had slipped back into a playlist. A message first. A casual line. Then another. Then, eventually, a call. The screen lit up with her name at an hour my phone had grown used to being ignored.

Her voice, when I answered, carried the same notes, but arranged differently. There was less unguarded laughter. More control. She asked about work, about life, about the cat, all the surface things that had once been the scaffolding for deeper ones. I responded in kind. We circled each other politely, you know the dance.

At some point, the conversation slipped toward the old subject.

“So,” she said, and I could hear the faint sound of cloth against microphone as she shifted the phone. “How’s your famous sleep-rescue kit? Have you expanded the inventory?”

The question was delivered lightly, almost teasing. I felt a small, irrational flare of panic, like someone had asked to see a room I had been throwing everything into for months.

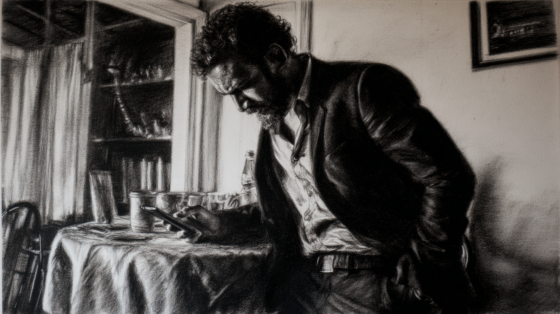

I could have lied. I could have said it was about the same. I could have described new items that didn’t exist. Instead, without thinking it through, I turned the camera toward the bedside table.

The image that filled the screen this time was not the same crowded arrangement she had laughed at months before. The table looked exposed. There was a circle of clean wood where something else had once stood and had not been replaced.

For a second, neither of us spoke.

I watched her face on the screen, the way the eyes narrow by a fraction of a fraction when the mind is connecting something it does not want to. Her lips pressed together, then parted as if to say something, then closed again. Her gaze flicked from the table to the camera and back, a small movement, but I noticed it nevertheless.

“You’re almost out,” she said finally.

The words were subdued, the tone neutral. If you played the audio without context, you might think she was making an idle observation. But there was a thinness in her voice I had not heard before, like a note pushed too far. What was that, it was neither pity nor judgement, but was it recognition? or perhaps realization?

She did not ask the follow-up questions. She did not ask if I had emptied the kit because I no longer needed it, or because I had stopped trying. She did not ask if I was sleeping now, or if the hour between 1 and 2 still caught me like a net. She took in the scene, let it sit between us, then shifted the conversation away with more care than she had used to enter it. Broken glass with spikes on them.

We spoke for a while longer. About other things. Things that could be closed without consequence. When the call ended, it did so gently.

The room returned. The fan kept clicking its small, regular judgment above me. The table stayed where it was, the empty kit arranged exactly as she had seen it. For the first time, I looked at it the way she must have, not as a collection of objects I had grown used to, but as a map of a choice I had been making without admitting it.

Maybe she chose, for her own sake, to read the kind version. Maybe she told herself that the empty kit meant progress, that the guy who had once kept an absurd assortment of remedies beside his bed had finally put some of them down and learned to rest. Maybe she needed to believe that people like us could reach the other side of exhaustion and stand there without holding on to every possible crutch.

Or maybe she saw what I see now. That the emptiness was not a sign that sleep had returned to me, but that I had given up on negotiating with it. That I had let the tools run out because even the act of trying felt like a promise I wasn’t sure I deserved. That the guy with the overflowing sleep-rescue kit had become a man who could not be bothered to refill it.

She did not call again after that, not like that anyway, there were a few messages, light and scattered, like someone checking that a door was still where they remembered it, without any real intention of walking through. Then even those stopped. Life closed over the gap her absence left, as it always does, with a kind of dull efficiency.

The hour, however, did not stop coming.

The fan still clicks. The table still holds its things but with an addition of a thin layer of dust on top. The box still slumps, that last strip still waiting, as if it believes being untouched might mean it is important. I lie here, in the same bed, in the same room, with the same sound circling above me, and I cannot get past the fact that there was one question she asked me, at this same hour, that I never answered.

Do people like us ever get to rest?

At 1:08 am, every night, the possible answers return, lining up politely in my mind, each one wearing the face of the man I could have been if I had chosen it. I do not speak them. I did not speak them then. I live, instead, in the space my silence created.

It’s 1:08 am and I can’t sleep.

Afterthought: This sat in my draft for more than a year, which reminds of the piece that has been sitting the longest in my drafts, its the tale of Amina’s Chicken, It’s been sitting for more than 12 years, I still have the original chatlog with Em, waiting for me to become the man I need to become to write it. Masha Dinka will publish it some time in the next 10 years.